A suture granuloma is a collection of scar tissue that forms around the sutures from an abdominal incision. It’s important to know what causes them and how they can be treated.

Abnormal lumps and bumps can be concerning, especially when they develop on the incision line after skin cancer surgery. While it’s important to visit a dermatologist about any unexplained growths that have suddenly appeared, it can be helpful to know that not all bumps indicate a serious problem. Suture granulomas, for instance, can appear on or near the area where stitches were placed during a past surgery.

This skin condition is simply a grouping of immune cells, most often caused by the sutures becoming embedded in the skin, or some of the material being left under the skin when the suture was removed. Granulomas can also form around a permanently placed medical device.

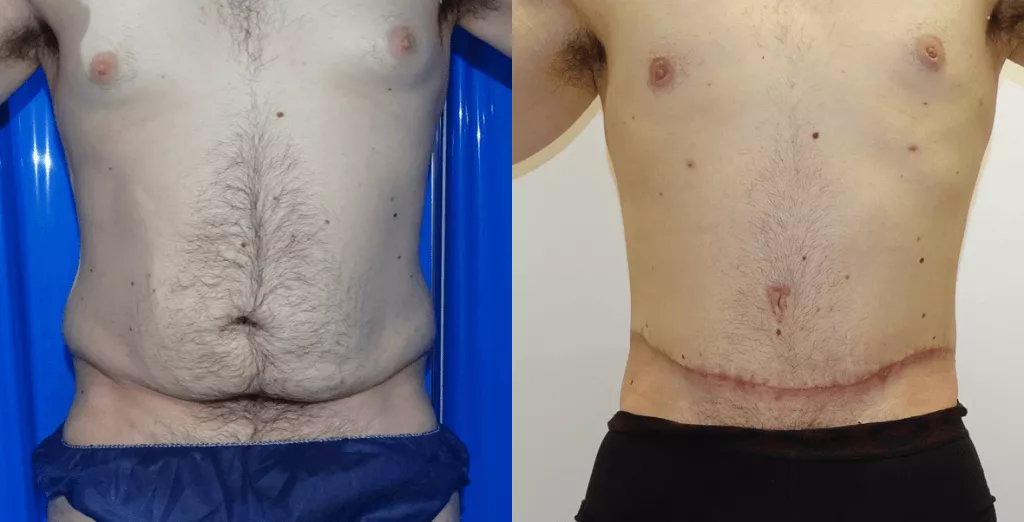

Suture Granuloma After Tummy Tuck

Suture granulomas develop from your immune system trying to create a barrier between the foreign material and your natural body tissues. Your cells begin to cluster as they completely surround the material or the general area of where it was removed. These granulomas tend to look red and swollen, and in some cases, the body tries to remove the material through the skin’s surface, creating what looks like a boil or pimple. Suture granulomas can occur right after surgery or, in the case of permanent devices, later on when the immune system delays its defense against the foreign object.

Your dermatologist should examine you to make a diagnosis, as with any unidentified skin growth. If it is determined you have a suture granuloma, there are a number of treatment options available. “Suture granulomas can resolve on their own, and simply monitoring it or using an anti-inflammatory agent may be all that’s needed,” says Dr. Mamelak, our dual board-certified dermatologist. In other cases, where the growth continues to get worse or becomes painful, the suture and granuloma can both be removed.

Keep in mind that if you have had a suture granuloma in the past, it is possible the growth can come back. As a result, you should consult with your physician before any future medical procedures.

In this guide, we review the aspects of Suture granuloma after tummy tuck, dissolvable suture granuloma, how to get rid of suture granuloma, and anti inflammatory cream for suture granuloma.

A suture granuloma occurs when a stitch in the skin gets infected, causing inflammation, redness, and pain. It can occur anywhere on the body where there is surgical incision. For example, if you have had surgery to remove a mole or other growth on your face or chest, you may hae experienced a suture granuloma at that site.

The good news is that most suture granulomas resolve on their own in 6-12 weeks (or sooner). If you have been experiencing symptoms of a suture granuloma after tummy tuck surgery—pain in the area of your incision and/or swelling—your doctor may recommend treatment with antibiotics to help speed up healing.

Suture granuloma after tummy tuck

My primary concern when operating is patient safety. Nevertheless all surgery carries the risk of complications. However, this risk is low. Complications tend to be rare and most complications are minor and resolve without the need for further surgery. If complications occur then I will manage the treatment of them.

I believe that my personal philosophy of keeping procedures simple, safe and conventional and my natural tendency to be a conservative surgeon helps to minimise the risk of complications and problems. I do not operate on patients who are unsuitable or who are high risk. Careful patient selection is important.

Some of the potential problems are discussed below.

All surgery entails incisions, which can bleed. Bleeding may be early or late, minor or major, and may require a return to the theater to eradicate a collection of blood, called a haematoma, and to control the bleed. Late bleeding can manifest as a seroma, a collection of fluid which may require repeated drainage with a needle and syringe.

Infections may be minor, presenting with redness, tenderness, pain and warmth, or they may be more severe with throbbing pain, swelling, pus collections, and high fever. Treatment options may include local wound care, surgical drainage, removal of implants, antibiotics or other secondary surgery. Where indicated, prophylactic antibiotics (antibiotics to prevent infection) are given during your surgery but usually not continued in the recovery period as this has not been shown to be beneficial.

Wounds dehiscence is splitting open of the wound or wound breakdown. This may be caused by infection, tension in the wound, foreign body in the wound, smoking, poor nutrition and so on. Once it has occurred, secondary suture is usually not advised as the wound is in a poor state to receive sutures. Usually wound breakdown is treated with keeping the wound clean and applying a daily dressing with an antiseptic. Antibiotics are not usually required. Later scar revision later is rarely required.

Suture abscesses appear initially as little irritable bumps in the scar. What you are feeling is the stitch. Suture abscesses are relatively common with buried dissolving sutures because an inflammatory response is necessary to cause the suture to dissolve. This process happens usually a few months after surgery. These bumps can progress to a small pustule which can breakdown and discharge. Sometimes suture material can be seen or felt. If suture material is evident then this should be removed as it causes inflammation and interferes with healing. Otherwise suture abscesses are treated as a wound dehiscence. Antibiotics are not usually required.

Bruising and swelling are normal following surgery and tend to resolve 2-4 weeks after an operation. In some patients or procedures, this can be prolonged. Bruising and swelling tend to subside following surgery. For example, patients who undergo facelift surgery may get bruised on their neck and chest, and tummy liposuction patients may experience bruised and swollen genitalia.

Dissolving sutures are frequently used for many surgical procedures. These sutures dissolve by the body develops an inflammatory reaction against them. Cells called phagocytes then literally eat the sutures away. Sometimes this inflammatory reaction can be close to the surface of the skin and manifest as a pimple. Removal of the suture usually causes the problem to resolve.

Every incision leaves a scar. Part of the art of plastic surgery is knowing where and how to place that scar so that it is well camouflaged and becomes inconspicuous. It should be kept in mind that scars take over a year to mature. During the maturation process, there is a phase when the scar becomes red and raised, usually from about 3 weeks after surgery to about 4 months. Sometimes hypertrophic or keloid scars can become excessively red and grow beyond this period, necessitating further treatment.

Nerves that carry sensory impulses from your skin may be cut, stretched, bruised or otherwise traumatised, thus causing numbness in the area operated on. Usually this is a transient phenomenon and sensation returns rapidly. One can expect most of the sensory recovery to occur within 6 weeks of surgery, although some degree of improvement may occur for up to 2 years.

Nerves also carry signals to the muscles, instructing them to move. Trauma to the nerves can result in paralysis of the muscles supplied. In most cases, as for sensory problems, this is transient and recovery occurs, but this can take up to 2 years after surgery. Permanent paralysis is rare after surgery.

Damage to other structures in the area

Salivary ducts, arteries, veins, etc. can all be inadvertently damaged during surgery. Although the utmost care will be taken, aberrant anatomy and other factors can lead to injury.

Anaesthetic related complications

During anaesthesia fluids, gases and drugs will be administered, and lines will be inserted. Although anaesthesia is much safer these days than it used to be in the past, anaesthesia still carries risks. The risk is probably equivalent to flying.

Lung infections, collapsed lungs, fluid imbalances, kidney problems, strokes, heart attacks and other events can occur or manifest as a consequence of surgery. Deep vein thrombosis is also a risk and is further discussed under Tourism, which lists advice to travellers. These problems are all rare, but are part of the risk of surgery.

Cosmetic surgery usually converts a fit healthy individual into a patient who has had surgery and requires time for recovery. In other words, you become sick. Although you may realise this beforehand, it is often difficult to adjust to and it is not unusual for patients to feel depressed, even tearful after surgery. Usually one’s mood improves as the swelling and bruising subside. Also, it is not unusual for an initial satisfaction with surgery to be followed by a period of nit picking and fault finding. This usually passes with time.

Unsatisfactory cosmetic result

Part of the difficulty of cosmetic surgery is for the surgeon to understand what it is that bothers you so that a proper correction can be attained. In this regard, it is important for you to find a plastic surgeon with whom you can communicate. You should understand that no person has an absolutely symmetrical body, that the face is different on the two sides; that the left breast tends to be broad and squat while the right breast is usually longer and thinner. Also, there is always the risk of too much, too little, too big, too small, irregularities, dents, bulges, etc. Human beings are not lumps of clay or bronze, which can be moulded, but living tissue, which can sometimes heal unpredictably.

dissolvable suture granuloma

A suture granuloma is a small mass of clustered immune cells that may develop around the site of a surgical procedure. It is a potential complication of surgery that can be an increased risk in certain cases, as some types of sutures appear to promote granuloma formation. In a patient with a history of surgeries, small masses must be evaluated with care to differentiate between benign and malignant growths, and it may be necessary to perform a biopsy to determine what kinds of cells are involved.

In the case of a suture granuloma, the immune cells cluster to create a wall between the rest of the body and a foreign object. The immune system may determine that sutures, staples, fixators, and other surgical devices are dangerous, and can use scarification and clumps of immune cells to isolate these materials. This can create the appearance of a lump at the suture site that may protrude from the skin and can appear red and irritated in some cases.

A granuloma can sometimes appear right after surgery, but it can also take time to appear as a result of the irritation that staples and permanent sutures cause. The patient may be concerned by the appearance of the lump and may report it to a medical professional. An evaluation can include a quick palpation, a discussion of the patient’s history, and a needle aspiration biopsy to find out what kinds of cells are involved.

If the growth is a simple suture granuloma, the medical professional may not recommend any treatment. In cases where the growth impedes movement or causes a cosmetic problem, it can be removed. After removal, the surgeon can recontour the skin to remove any lumps or dips, and may recommend the use of compression bandages and other tools to limit the development of another lump. Sometimes, however, the granuloma may become recurrent, and it could create a lifelong problem for the patient.

Patients should monitor their surgical sites carefully for issues like heat, swelling, changes in skin color or texture, and strange growths. Surgeons prefer to err on the side of caution and can examine a patient with concerns about anything occurring at the site of an incision. Since this type of granuloma can mimic a more invasive growth, and vice versa, it is important to accurately diagnose the growth with the assistance of a biopsy to determine whether it is a risk.

Are Suture Granulomas Rare?

Due to advances in surgery and the sutures used today, suture granulomas do not occur often. Silk sutures that the body can’t absorb may result in surgical granulomas in up to 7 percent of surgeries. With reduced use of non-absorbable silk sutures, which can result in higher rates of suture granulomas, the rate of these growths dropped.

Suture granulomas occur more often in surgeries close to the skin, such as Mohs surgery for skin cancer. Since suture granulomas can occur years after surgery, patients may not think surgical sutures are the cause. Suture granulomas may seem like unexplained growths at first glance.

Is a Suture Granuloma the Same as a Keloid?

Keloid scars are raised spots that can develop after a skin injury, usually on the shoulders, earlobes, cheeks, or chest. Suture granulomas are an inflammatory reaction by the body to the stitches or staples used to close surgical wounds. Keloids are reactions to an injury, while granulomas react to the sutures.

Neither of these skin conditions is harmful unless infected, but they might be painful or unsightly enough to prompt their removal. Talk to a doctor or a dermatologist if you would like to get your keloid scar or suture granuloma treated.

Is a Suture Granuloma the Same as a Post-Surgical Seroma?

A post-surgical seroma is a sterile buildup of fluid underneath the skin, typically at the site of an incision. Seromas can look swollen, and may feel tender or sore. Like suture granulomas, post-surgical seromas will usually go away on their own, but if one is large or causing pain, your doctor may decide to drain it.

To tell the difference between a suture granuloma and a post-surgical seroma, examine the area of the growth. If it is around a suture and does not cause pain, it is probably a granuloma. If it looks like a raised lump underneath the skin near the incision site and is slightly painful, it is probably a seroma.

Suture Granuloma Treatment

Is a Suture Granuloma the Same as a Scar?

No. Suture granulomas are a buildup of immune cells, while scars are a buildup of tissue. While suture granulomas will disappear with time or treatment, scars are often permanent, depending on the severity of the wound.

There are also a few different types of scars, including keloid, hypertrophic, pitted, and contracted scars. Each type depends on the type of injury you have sustained. You can treat scars through massage, pressure dressings, silicone gels, or professional help, but a scar will likely remain with you for the rest of your life.

Are Suture Granulomas Painful?

Most suture granulomas are not painful. A doctor should examine painful suture granulomas because the pain might be a sign of infection.

A dermatologist may surgically remove painful suture granulomas that don’t respond to anti-inflammatory treatments, oral steroids, or antibiotics.

How Can I Prevent Suture Granulomas?

You can’t necessarily prevent suture granulomas, but there are plenty of things you can do to take care of your wound while it heals. Take painkillers to relieve pain and swelling. Keep the wound moist to prevent and lift any scabbing, and to promote skin cell regeneration. Treat the area with care, as the skin will be delicate, even after your doctor removes the stitches.

Is Infection Common After Surgery?

If you have an unusual growth or scarring after surgery, you may be worried that your wound has become infected. Luckily, there is only a 1-3% chance that you will develop a surgical site infection (SSI). The infection could be at the surface level, within the incision, or in the organs.

Signs of an infection include redness, delayed healing, warmth around the wound site, tenderness, fever, pain, and swelling. Sometimes, wounds may discharge pus. If you believe that you have an SSI, contact your doctor immediately. Antibiotics treat infections, but it’s important to catch them early on.

how to get rid Of suture granuloma

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity is not elevated in a songbird (Junco hyemalis) preparing for migration

During spring, increasing daylengths stimulate gonadal development in migratory birds. However, late-stage reproductive development is typically postponed until migration has been completed. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis regulates the secretion of glucocorticoids, which have been associated with pre-migratory hyperphagia and fattening. The HPA-axis is also known to suppress the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis, suggesting the possibility that the final transition into the breeding life history stage may be slowed by glucocorticoids.

We hypothesized that greater HPA-axis activity in individuals preparing for migration may foster preparation for migration while simultaneously acting as a “brake” on the development of the HPG-axis. We checked this idea by measuring the amounts of corticosterone (CORT), CORT that is increased during stress, and negative feedback in dark-eyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis) in a population that stays together all winter and has both migratory (J.h. hyemalis) and resident (J.h. carolinensis) birds.

We predicted that, compared to residents, migrants would have higher baseline CORT, higher stress-induced CORT, and weaker negative feedback. Juncos were sampled in western Virginia in early March, which was about 2–4 weeks before migratory departure for migrants and 4–5 weeks before first clutch initiation for residents. We were wrong when we said that migrants would have higher baseline and stress-induced CORT, but they had the same negative feedback effectiveness as residents. This suggests that various physiological processes are the root cause of migrants’ delayed breeding. Our findings also suggest that baseline CORT is not elevated during pre-migratory fattening, as migrants had lower baseline CORT and were fatter than residents.

Identification and signaling characterization of four urotensin II receptor subtypes in the western clawed frog, Xenopus tropicalis

Through the UII receptor (UTR), urotensin II (UII) is involved in a lot of healthy and unhealthy processes, such as vasoconstriction, movement, osmoregulation, immune response, and metabolic syndrome. In silico studies have revealed the presence of four or five distinct UTR (UTR1–UTR5) gene sequences in nonmammalian vertebrates.

However, the functionality of these receptor subtypes and their associations to signaling pathways are unclear. The western clawed frog (Xenopus tropicalis) was used in this study to get full-length cDNAs for four different UTR subtypes: UTR1, UTR3, UTR4, and UTR5. When homologous Xenopus UII was put on cells that expressed UTR1 or UTR5, it made calcium move around inside the cells and phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Cells expressing UTR3 or UTR4 did not show this response.

Furthermore, UII induced the phosphorylation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB) through the UII–UTR1/5 system. Since cAMP did not accumulate inside the cells, it is likely that a different signaling pathway than the one involving Gs protein is what causes UII-induced CREB phosphorylation.

Giving UII to cells, on the other hand, increased the phosphorylation of GEF-H1 and MLC2 in all UTR subtypes.e results define four distinct UTR functional subtypes and are consistent with the molecular evolution of UTR subtypes in vertebrates. Further understanding of signaling properties associated with UTR subtypes may help in clarifying the functional roles associated with UII–UTR interactions in nonmammalian vertebrates.

Neonatal tactile stimulation decreases depression-like and anxiety-like behaviors and potentiates sertraline action in young rats

It is well known that events which occur in early life exert a significant influence on brain development, which can be reflected throughout adulthood. The purpose of this study was to find out how neonatal tactile stimulation (TS) affected behavioral and morphological responses related to depressive and anxious behaviors after sertraline (SERT), an SSRI, was given.

Male pups were subjected to daily TS, from postnatal day 8 (PND8) to postnatal day 14 (PND14), for 10 minutes every day. On PND50, adult animals were subjected to forced swimming training (15 min). On PND51, half of each experimental group (UH and TS) received a single sub-therapeutic dose of sertraline (SER, 0.3 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) or its vehicle (C, control group). Thirty minutes after injection, depression-like behaviors were quantified in a forced swimming test (FST, for 5 minutes. The following day, biochemical tests came first, then assessments of anxiety-like behaviors in an elevated plus maze (EPM). TS per se increased swimming time, decreasing immobility time in FST.

Besides, TS per se was able to increase the frequency of head dipping and time spent in the open arms of EPM, resulting in a decreased anxiety index. In addition, groups exposed to TS showed decreased plasma levels of corticosterone per se. It is interesting that TS exposure greatly increased the antidepressant effects of a subtherapeutic dose of SERT. However, this drug could also increase the anxiety-reducing effects of TS, as seen in FST and EPM.

Lower levels of corticosterone and cortisol in the plasma of animals that were exposed to TS and then given SERT show that this neonatal handling and the antidepressant drug have an interesting interaction.

From our results, we conclude that neonatal TS is able to exert beneficial influence on the ability to cope with stressful situations in adulthood, preventing depression and favorably modulating the action of antidepressant drugs.

Dietary total antioxidant capacity is related to glucose tolerance in older people: The Hertfordshire Cohort Study

Dietary antioxidants may play a protective role in the aetiology of type 2 diabetes. However, observational studies that examine the relationship between the antioxidant capacity of the diet and glucose metabolism are limited, particularly in older people. We aimed to examine the relationships between dietary total antioxidant capacity (TAC) and markers of glucose metabolism among 1441 men and 1253 women aged 59–73 years who participated in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study, UK.

Diet was assessed by food frequency questionnaire. To figure out dietary TAC, we used published lists of TAC measured by four different tests: ORAC (oxygen radical absorbance capacity), FRAP (ferric-reducing ability of plasma), TRAP (total radical-trapping antioxidant parameter), and TEAC (trollox equivalent antioxidant capacity). Fasting and 120-min plasma glucose and insulin concentrations were measured during a standard 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.

In men, dietary TAC estimated by all four assays was inversely associated with fasting insulin concentration and homoeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR); with the exception of ORAC, dietary TAC was also inversely related to 120-min glucose concentration.

There were no associations with fasting glucose or 120-min insulin concentrations. In women, with the exception of the association between ORAC and 120-min insulin concentration, dietary TAC estimated by all assays showed consistent inverse associations with fasting, 120-min glucose and insulin concentrations and HOMA-IR. These associations were more marked among women with BMI ≥30 kg/m2.

These findings suggest dietary TAC may have important protective effects on glucose tolerance, especially in older, obese women.

Peritoneal Closure Over Barbed Suture to Prevent Adhesions: A Randomized Controlled Trial in an Animal Model

to look at how adhesions form and the histological features of peritoneal closure and nonclosure over a barbed suture placed inside the abdomen.

Single-blind randomized controlled trial (Canadian Task Force Classification I).

Certified animal research facility.

Abdominal cavities were entered via midline incision. The left and right parietal peritoneal surfaces were cut 1.5 cm apart and stitched with 3/0 V-Loc unidirectional barbed suture material. The parietal peritoneum was approximated over the barbed suture using polypropylene suture material (7/0 Prolene) to embed the barbed suture (peritonization) on one side, and left open on the other side. The side of the barbed suture to be peritonized was allocated at random. On postoperative day 32, all rats were sacrificed, adhesion formations on each side were macroscopically scored, and histological features were evaluated microscopically.

The median adhesion score was 2.00 (range, 1–4) on operative fields. There was no statistically significant difference in median adhesion score between the peritonized and nonperitonized sides (1.5 vs 2, respectively; p = .13).

There were no statistically significant differences in the median scores for acute and chronic inflammation between the peritonized and nonperitonized sides (p =.58 and p =.45, respectively). However, the median score for fibrosis was significantly higher on the peritonized side (3 vs. 1.5, respectively; p =.02).

Based on the results of this study using rats as models, using barbed suture material intra-abdominally may lead to adhesions that can not be stopped by peritonization.

Consistent individual variation in day, night, and GnRH-induced testosterone concentrations in house sparrows (Passer domesticus)

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis controls the release of testosterone. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) starts the endocrine cascade. Testosterone, through its pleiotropic effects, plays a crucial role in coordinating morphology, physiology and behavior in a reproductive context. The concentration of circulating testosterone, however, varies over the course of the day and in response to other internal or external stimuli, potentially making it difficult to relate testosterone sampled at one time point with traits of interest.

Many researchers now utilize the administration of exogenous GnRH to elicit a standardized stimulation of testosterone secretion. However, it has remained unclear if and how this exogenously stimulated activation of the HPG axis is related with endogenously regulated testosterone that is capable of influencing testosterone related traits. Repeated measurements of a hormone can show that differences between individuals in hormone levels at the HPG axis level are consistent. These differences may be caused by genetic differences in a population that is exposed to the same environmental cues. Thus, we asked, using the house sparrow (Passer domesticus), how daily endogenous variation in testosterone profiles relates to GnRH-induced testosterone secretion.

Further, we explore the relationship between endogenous daily testosterone peaks and GnRH-induced testosterone with badge size, a morphological trait related with status within a social group. We found that GnRH-induced testosterone levels reflect a highly repeatable hormonal phenotype that is strongly correlated with nighttime testosterone levels.

The results show that GnRH-induced testosterone can be useful in studies that want to learn more about how endogenously regulated testosterone levels vary from person to person and how important nighttime testosterone levels might be for physiology and behavior.

anti inflammatory cream for suture granuloma

There are several types of anti-inflammatory creams that may be used to treat suture granulomas, but it is important to note that these creams are not a first-line treatment for this condition. If you have a suture granuloma, it is important to seek medical evaluation and treatment from a qualified healthcare provider.

That being said, anti-inflammatory creams such as corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be prescribed by a healthcare provider to help reduce inflammation and pain associated with suture granulomas. These creams can be applied topically to the affected area and can help to reduce redness, swelling, and discomfort.

It is important to follow your healthcare provider’s instructions for using these creams, as overuse or misuse can cause side effects such as skin thinning, discoloration, and increased risk of infection.

Other treatments for suture granulomas may include surgical removal of the granuloma or antibiotics if the granuloma has become infected. It is important to discuss all treatment options with your healthcare provider to determine the best course of action for your individual case.